“It was The Stand. I was 16 years old. It was the peak of the Stephen King miniseries era, and it was appointment television. My whole family watched it on the first airing, and I was enraptured. I vividly recall the excitement at school the following day – everybody was watching it and we were hanging on every minute. It remains the high water mark of the King miniseries. I remember seeing Mick’s name in the credits and committing it to memory.”

That’s Mike Flanagan, one of the most talented voices in horror after movies like Oculus (2013), Hush (2016), Ouija: Origin of Evil (2016), Gerald’s Game (2017) and Doctor Sleep (2019) and Netflix series like The Haunting of Hill House (2018), The Haunting of Bly Manor (2020), Midnight Mass (2021) and the forthcoming adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher.

And he’s talking about Mick Garris, a name as synonymous with the horror genre as Hooper, Carpenter, Romero or Craven, a figure who’s been in the industry for half a century, 37 of them as a writer, producer and director.

Like Flanagan and legions of other Gen Xers who witnessed Garris’ adaptation of Stephen King’s post-apocalyptic epic when it aired in 1994, Moviehole similarly committed Mick’s name to memory.

Back before you could look someone up on the Internet Movie Database, seeing a director’s name and figuring out what else they’d worked on wasn’t so easy. But throughout the rest of the 90s, horror fans kept seeing Garris’ name on some amazing things.

He wrote the short film that accompanied Michael Jackson’s Ghosts (1996) along with Stephen King, Jackson himself and the late practical effects maestro Stan Winston (who directed).

(It wasn’t Garris’ first work with Jackson – incidentally – He’d been one of the zombies crawling out of his grave to pursue Michael and Ola Ray in the Thriller video back in 1983).

A year later Garris and King trod very hallowed ground when they made their own version of The Shining, King having famously disliked Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 adaptation. The author wrote the script, Garris directed and it appeared on ABC, the studio behind The Stand, over three nights in April 1997 (it wasn’t shown on TV in Australia, releasing instead on DVD).

But when everything about a writer or directors’ work was finally available at the click of a mouse, it was suddenly apparent what a long shadow Garris cast not just over horror but the entertainment industry.

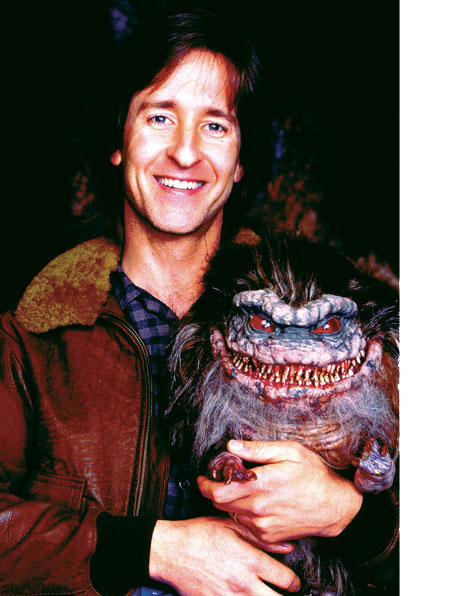

He got his start on Amazing Stories in the 80s, a TV show which bought together names like Bob Zemeckis, Irvin Kershner, Brad Bird, Tobe Hooper, Joe Dante, Peter Hyams and Kevin Reynolds (and in many cases, introduced them to a whole new audience of devotees of the Spielberg aesthetic). He directed one of the Psycho sequels in 1990. His first film as a director was Critters 2 in 1988. He directed an episode of Tales From the Crypt in 1994. He Wrote *batteries not included in 1987 and The Fly II (1989).

But to many who paid attention to movements behind the scenes, Garris had the coolest job in the business simply as Stephen King’s de facto director in Hollywood – after starting with King’s Sleepwalkers (1992), he’d go onto adaptations of Quicksilver Highway (1997), Riding the Bullet (2004), Desperation (2006) and Bag of Bones (2011).

Whoever Garris was, it was obvious he was connected, and he’s been high on our wishlist of interviews since before Moviehole.net existed.

Finally telling his story

We finally got our chance late last year with the publication of Master of Horror, the official biography about Garris written by his long-time friend and colleague, entertainment journalist Abbie Bernstein.

At 391 pages it’s a doorstop to rival plenty of Stephen King’s novels, but what you don’t know about Mick Garris’ life, times and career when it’s over isn’t worth knowing.

It might be the most comprehensive record of anyone’s work we’ve ever read, let alone an artist in Hollywood.

Bernstein goes down every possible rabbit hole of Garris’ past from his family and upbringing in his native Los Angeles, the influences and art that formed him, his early years as a movie reporter, his past music career, his early start in the industry, TV, movie and novel projects and his podcast, all of it in exhaustive detail.

In fact, Bernstein goes so deep she doesn’t just dive into every movie and series he’s worked on. In the case of his seminal horror anthology Masters of Horror (2005-2007) she talks about the ins and outs of every individual episode.

Since Hollywood personalities have been locked inside with nothing to do like the rest of us thanks to COVID, we’ve seen a bigger rash of movie and entertainment memoirs than ever.

Actors and filmmakers as varied as Mel Brooks, Seth Rogen, John Wood, Oliver Stone, Michael J Fox, Leonard Maltin, Ron and Clint Howard and countless more have all got in on the act. Yet the biography of Mick Garris – a writer himself – was written by someone else. Why?

Garris sat down for an hour-long video chat with Moviehole.net from his home base in LA’s San Fernando Valley about the book, his career and everything else and he couldn’t have been more pleasant to talk to (more about Garris’ infamy for niceness is below), but our first question was why he’d outsource something so personal.

“It’s really hard to make films and television. The hours suck and if you can’t be completely committed to surrounding yourself with creative people and trying to make something special, what’s the point?”

“I’ve had other people ask about doing a biography, and I just couldn’t imagine anyone would be interested,” the 70-year-old horror legend says. “But I’ve known Abbie for 40 years. She proposed it a few years ago and I said ‘if you get a publisher then yes, I’ll do it’. So I lived to rue the day… No [kidding] I thought she did such a great job of it. She really did all homework so it made it unnecessary for me to write an autobiography.”

What’s even stranger about Garris not writing his own story however is the fact that he’s no stranger to long form writing as well as screenwriting – he’s in fact an accomplished novelist as well.

“I’m just a little churlish about the value of my own story,” he says. “I mean, everyone has one and they’re all worth telling, but my professional story is actually the story of a lot of great, talented people I’ve been lucky enough to work with.”

He also says that despite his deep involvement, Bernstein did all the heavy lifting. “Because of the format it’s almost a verbal autobiography because so much of it’s in the first person. So I feel like I’ve written an autobiography even though it was through the fingers and talents of Abbie Bernstein. But when I’m writing I’d much rather tell a story than talk about my own life.”

The nicest guy in Hollywood?

So, to Garris’ niceness. It’s an issue, but not how you think.

Most entertainment people are on their best behaviour when facing the press so you can’t really take their conduct in interviews as gospel truth about what they’re like.

But in an industry full of two-faced circle jerks about how wonderful everyone is and how everyone ends up like family even though you just know they’re stabbing each other in the back at every turn – it’s one of the principles Hollywood was built on, after all, everyone – and we mean everyone – is so effusive talking about what a nice guy Garris is, going beyond mere lip service, it’s hard not to believe it.

In conversation he’s funny, whip smart, self-effacing, incredibly knowledgeable about his craft, seems genuinely interested in talking to you and can’t hide his love for what he does and the people he does it with.

His company is called Nice Guy Productions, and if it was anyone else in the business it’d seem trite and a little forced, but in this case it’s almost as if the universal praise and love for Garris appointed the name for him.

“I am a fan. I learn all the time and enjoy meeting people I admire, whether I know them or not. I enjoy talking about what makes them who they are, what drives their creative muses, how they work.”

And after having an interview with him on our bucket list for so long, Moviehole.net couldn’t have been gladder to finally see just how nice a guy he is. “Mick’s kindness is a rare thing,” Flanagan agrees. “It’s absolutely genuine, utterly unforced and has persisted unchanged for decades in an industry that can break people down into their worst selves in a matter of a months.

“His love for the genre is so great he seems to celebrate everyone’s contributions. He’s authentically delighted by the work of his peers in a business where competition and jealousy can be overwhelming. He carries this sense of community wherever he goes, and as you make your way through the industry you see the same smiles on people’s faces when they speak about him. Everybody knows Mick and I’ve yet to meet a single person who doesn’t love him.”

If you put a sentiment like that to Garris he just smiles, pleased but a little embarrassed by such adulation, and immediately turns it back on peers he’s worked with, saying ‘There are plenty of great people in this business or I wouldn’t have a career’.

Origin story

If you’re enough of a fan of Garris’ to have read or listened to whatever you can find about him (including his insightful and entertaining podcast Post Mortem – more below), the things he’s done and places he’s worked are industry lore.

When Star Wars had been released and was becoming the cultural juggernaut we know today, George Lucas rented an office in a strip mall near the Universal Studios main gate to manage the various production and publicity functions not handled by the studio that bankrolled the film, 20th Century Fox. Garris got the gig as a receptionist, answering phones and manning the front desk.

But being such a small, informal operation, he got to play with some of the coolest toys and perform the coolest duties in Hollywood before most of us knew they existed.

During the 1978 Oscars, when R2D2 and C3PO appeared on stage with Mark Hamill to present the Oscar for sound effects editing for 1977’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Star Wars got a special achievement award for sound), Garris controlled the R2 model remotely from the wings.

But even before Star Wars came his film journalism, pursued because of a fascination and love of the medium. College magazines and his own self-published trade press periodicals contained words of wisdom from however many of his heroes Garris could wrangle. Later he’d reproduce the concept for his own talk show on Channel Z, a long defunct public access station in Los Angeles.

And the whole time he wrote, wrote, and wrote some more until someone at Amblin Entertainment, Steven Spielberg’s company, read a script of his and gave Garris his break. Before he knew it he was writing on Amazing Stories, the iconic 80s anthology series (work for which he won an Edgar Award), and he’s never looked back.

Because of his long-time collaboration with Stephen King and the fact that he was the driving force behind two-season anthology Masters of Horror, it’s natural to think of Garris as a horror guy – indeed, most of the guests on his podcast are notable names from the horror or fantastical genres.

But he’s much more of an entertainment geek in general than just a horror devotee. It might surprise you to learn he wrote Better Midler/Sarah Jessica Parker/Kathy Najimy witchcraft romp Hocus Pocus (1993), which is so much a perennial favourite at Halloween Disney are making a series about it for Disney Plus (Garris isn’t involved but wishes them well).

He visited Australia in 2000 to shoot a pilot for a show called Lost in Oz (yes, based on the titular Wizard) that starred former soap princes turned horror fixture Melissa George in a darker take on the mythical land. He’s talked before about an episode of TV fantasy drama Once Upon a Time he directed being among the most personal work he’s done. Clearly, we’re talking about a man of varied tastes and talents.

But what’s most apparent during our talk is that however synonymous he is with the horror genre, what defines Garris most is the people. “You appreciate the relationships more than anything else,” he says. “People are so important.”

He was particularly reminded of that in helping Bernstein with Master of Horror, when the process prompted fond memories of so many past projects. “Meeting and working with Clive Barker, Stephen King, Steven Spielberg – my gods of fiction and film, and to be able to have them be a part of my creative life was really great,” he says.

“But it also allowed me to appreciate the things I did without them like Masters of Horror, bringing that to life and gathering together such great filmmakers, many of whom had been creatively abused for years and not allowed to do the work that inspired them.”

And if it isn’t Master of Horror (or Masters of Horror) that generates warm fondness for past connections, it’s the adulation he gets at festivals and conventions, fan love that he seems to feel offsets the inevitable downsides of a career behind the camera. “I’ve earned my humility. There have been failures and successes, but I can appreciate even more how meaningful things I’ve been part of have been in people’s lives.

“To have written a movie like Hocus Pocus that’s so iconic today, way more popular than it ever was when it came out. The Stand was the highest rated TV miniseries of all time and people still talk about it, it has such a following.

“Even my first movie, Critters 2 [1988], is way more popular now than it ever was. When I went to see it opening day there were three people in the theatre. I felt like my career was over before it started. But mostly it just brings back all these relationships you make when you’re on a project.”

Masters of Horror

But the book is called Master of Horror and the TV series he built from the ground up is called Masters of Horror, so for better or worse it’s the genre Garris is most associated with, something that – as endlessly humble and grateful as he is – he’s fine with.

The 2005 series was something of a Grand Unified Theory of Mick Garris, the culmination of everything he loved and wanted to achieve in the genre. No, he didn’t want to write and direct every episode (although his name’s on two of them), he simply wanted to champion a genre he loved and give a platform to the artists he respected – people who, having toiled in the least respected genre in Hollywood, had spent their careers battling to have their visions realised on screens.

Garris gave legends like John Carpenter, Larry Cohen, Tobe Hooper, Stuart Gordon, Dario Argento, John Landis, Don Coscarelli, Takashi Miike and Peter Medak the money, space and creative freedom to tell the stories they wanted to tell, the 26 part series written by those above as well as Garris himself, Clive Barker, Sam Haam (of Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman), Max Landis (son of John), genre legend Richard Matheson and past horror masters like HP Lovecraft and Ambrose Bierce.

It was a professional expression of what had started as a series of friendly dinners out. The first one, at Café Bizou in Sherman Oaks, had Garris, John Landis, John Carpenter, Guillermo del Toro, Garris’ friend Bill Malone, Tobe Hooper, Larry Cohen, Stuart Gordon, Don Coscarelli and actor Bob Burns.

When a neighbouring table sang ‘Happy Birthday’ to a member of their party, Garris and company joined in. At the end of the song, del Toro stood and loudly wished the guest of honour a happy birthday ‘from the masters of horror’. The name stuck.

In recent years we’ve lost some of those directors who – despite being so beloved by fans – never got their due from Hollywood’s paymasters. Garris in particular remembers Tobe Hooper (1974’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, 1982’s Poltergeist, the criminally underrated Lifeforce, 1985) because the late director’s episodes of Masters of Horror episodes were among the last projects he made before his 2017 death.

Together with being self-depreciating about his own creative achievements, he almost seems prouder of the work he allowed such greats to do on Masters of Horror. To Flanagan, the pleasure Garris takes in championing the artists he loves is the secret to his success.

“Mick has two essential traits – a genuine and consuming love of horror and an impeccable reputation. He’s spent years pulling together a bona fide community of horror creators. He’s a very talented filmmaker but he’s also a catalyst. He brings people together and keeps them together. He’s built this network so his legacy goes beyond his work.”

In fact, it can be argued that it’s Garris’ work away from regular writing and directing that’s contributed even more to his career-long effort to share his love of horror with anyone who’ll listen.

After his early stint as a Star Wars receptionist, he drifted into a self-made specialisation shooting behind-the-scenes footage for making-of featurettes – the sort of thing that would play on TV variety shows years before DVD extras were dreamed of. Among them were documentaries about The Fog (1980), The Howling (1981) The Thing (1982), Indiana Jones and The Temple of Doom (1984) and The Goonies (1985).

Since then, it seems like anywhere there’s been either an iconic horror project or a way of talking about them, Garris has been involved. He’s been part of Joe Dante’s Trailers From Hell, he directed an episode of anthology series Tales From the Crypt (1994), he was a consulting producer on Eli Roth’s series History of Horror (2018)… the list goes on.

But nowhere is his love of the genre and the people in it more obvious than in his podcast, Post Mortem. Sharing the name with the show he hosted for Fear.net (now part of SyFyWire.com) from 2010 to 2016, the approach is the same. He gets some of the most iconic and influential writers, actors and directors from the genre and puts them on ‘the slab’ to cross examine them about their work.

The roll call is long and impressive; Joe Dante, John Landis, Karyn Kusuma, Walter Hill, Eli Roth, Don Coscarelli, Roger Corman, Stuart Gordon, Neil Marshall, Mike Flanagan, Jeffrey Coombs, former New Line Cinema head honcho Bob Shaye, Dario Argento, David Slade, Oren Peli, John Carpenter, Darren Lynn Bousman, Alexandre Aja, Sean S Cunningham, Ari Aster, Peter Medak, Fred Dekker, David Cronenberg, Henry Thomas, Barbara Crampton, Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, Lynn Shaye, makeup maestros Howard Berger and Greg Nicotero, Lloyd Kaufman, Matt Frewer, Guillermo Del Toro, author Joe Hill, Josh Boone (who created and directed the recent nine-episode remake of The Stand), Nicholas Meyer, Ron Perlman, Clancy Brown, Adam Wingard, Clive Barker, Frank Darabont, Kevin Smith, Neill Blomkamp, The Soska Sisters, Julia Ducournau (Raw), Edgar Wright, Tom Savini, Alice Krige, Kevin Williamson, Carl Gottlieb (Jaws screenwriter) and many more.

“I’m just a little churlish about the value of my own story. I mean, everyone has one and they’re all worth telling, but my professional story is actually the story of a lot of great, talented people I’ve been lucky enough to work with.”

Speaking to even one of the creators of so much of the entertainment we love would be enough to blow the mind of most movie geeks, but for Garris… Well, here’s the thing; his mind is blown too. His real superpower isn’t being nice. It’s that he’s one of us.

He told the story on Post Mortem once of a limousine ride onto the Universal studio lot accompanied by Steven King, the pair bound for Steven Spielberg’s office to meet about a possible project. King said, “If only everyone out there knew we were going to a meeting with Steven Spielberg!”, and Garris quickly countered with; “If only those people out there knew that I was in a limo with Stephen King to go to a meeting with Steven Spielberg!”

He’s the movie geek who got a foot in the door and a seat at the table, a horror addict who found himself on the inside.

When we tell him one of the things we love about Post Mortem is because he approaches it not like a Hollywood type but a fan, he’s unhesitant. “I am a fan,” he agrees. “I learn all the time and enjoy meeting people I admire, whether I know them or not. I enjoy talking about what makes them who they are, what drives their creative muses, how they work.

“The thing is, unless you hire a director friend to do a cameo in your movie or something like that, directors don’t work together. To be able to learn how others do it is a great education for me, even at this stage of my career. I’ve been directing since I was 33 and I just turned 70 but I still feel like that 33-year-old starting out, being inspired by people I admire.”

Making a stand

But Garris’ work in other media still has a hard time overshadowing his very real accomplishments as a director, and he’s enjoyed milestones many filmmakers would kill for. One in particular…

To set the stage; it was a golden age in TV miniseries by the mid 90s. The finale of the 1977 adaptation of Alex Haley’s slavery drama Roots was the most watched miniseries event in history, with 100 million viewers (almost half the US population at the time).

A couple of years later, 1982 nuclear war fable The Day After was such a cultural phenomenon it was distributed theatrically in many territories including Australia, despite being made for TV. A year later Goodbye, Farewell and Amen, the final M*A*S*H episode, drew 121 million viewers.

Stephen King’s status as a force in movies and TV was given a giant, red-wigged shot in the arm with the 1990 version of It, with Tim Curry unsurpassed as Pennywise the clown. Directed by Tommy Lee Wallace, 30 million people watched it over two nights.

The success of It then paved the way for The Stand. ABC spent $26m – an unheard amount for a TV series – and Garris wrangled over 120 speaking parts in 90 locations. The only way to do it was at breakneck speed, using 16mm film and covering at least two locations every day, many of which Garris hadn’t even seen prior to shooting.

Each instalment, airing between May 8 to May 12, drew 19 million viewers each. It’s high on the list of most-watched fictional television to this day, and unless you’re a Marvel or a Star Wars movie, it also puts most cinema attendance measures to shame as well.

It was something audiences had never seen before – an epic, Tolkien-level tale of good versus evil we’d normally only see on movie screens, and after Wallace made It a timeless classic, the world was ready and eager for another ‘good’ King adaptation.

Because it’s easy to forget the variable nature of films based on King’s books was already deeply entrenched by then. For every Carrie (1976) there was a Cat’s Eye (1985), for every Stand By Me (1986) there was The Langoliers (1995) and for every The Shawshank Redemption (1994) there was a Children of the Corn (1984)…

But The Stand is still a well-deserved classic, standing head and shoulders above Josh Boone’s recent do-over for Amazon (in which Garris has an uncredited cameo as a partygoer at a barbecue).

All of which begs a simple question. We’ve had new versions of It (2017), Pet Sematary (2019) and Carrie (2013). We’ve finally had a version of King’s famously unfilmable novel Gerald’s Game (2017), bought to life brilliantly by Mike Flanagan. We’ve had Doctor Sleep (2019), also by Flanagan and The Dark Tower (2017), the less about which is said the better.

“There are plenty of great people in this business or I wouldn’t have a career.”

New remakes of Firestarter, The Dark Half, The Tommyknockers and Christine are all coming up. Now we’re in what might be called the third wave of King adaptations, does Garris wish they’d call him, even for advice on how to do one right?

“Wouldn’t that be nice?” he laughs. “Everyone wants to work with the new model, and that’s fine. There are great opportunities for female directors and directors from different ethnicities now and I completely support that. I’ve been able to create my own career in so many ways, I’m lucky to still be vertical and creating.”

At the very least, surely it’s frustrating for him when they constantly revisit King’s work (or any other horror classic for that matter – and nowadays that list is very long) and it falls short, especially when it’s already been done well? The recent remake of The Stand for Amazon was fine enough, but it didn’t have the distinctive mise-en-scène of the original.

Now we also have to worry about yet another version of Salem’s Lot, the gold standard for terrifying television bought to immortal life by Tobe Hooper in 1979. Any list of the scariest scenes in horror could easily contain the recently deceased Ralphie Glick outside his brother Danny’s bedroom window or the moment when Barlow appears in Ned Tibbits’ prison cell – and keep in mind they were both on network TV.

But as Garris reminds us, we go through phases. There was already a 2004 TV remake of Salem’s Lot starring Rob Lowe as hero Ben Mears filmed entirely in Melbourne and central Victoria. And, as he adds, the reason to remake something is because it’s a good idea, regardless of how many times it’s already been adapted. That partly explains why King stories keep coming around again and again.

“I believe in seeing what somebody new brings to the mix,” he says. “I don’t resent anybody revisiting a project if it’s been long enough. The ones that weren’t really successful are the ones where they should have brought something more to it than they did at the time. A lot of people think the Kubrick version of The Shining is a classic and people generally know Stephen King hated it because it was so far from what he intended in the book.”

Ironically – and in the ultimate proof that not even the author of a work gets the definitive say about it in pop culture – the 1997 miniseries version King wrote and Garris directed, starring Steven Weber and Rebecca de Mornay, certainly worked and certainly adhered to the book’s themes (which Kubrick ignored), but few people think it holds a candle to its 1980 predecessor.

On horror

Also somewhat ironically considering he’s best known for adaptations, Garris is quite up front about wishing there were more original stories around. One glance at the horror genre might make you sigh in resignation – it’s all connected universes (The Conjuring), lazy remakes (Poltergeist) and so many do-overs it’s easy to lose track of which one we’re up to (Scream, Halloween, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre – which is up to its third franchise reset in a series of nine film… we think!).

But then you might remember Get Out (2017), The Babadook (2014), Hereditary (2018), It Follows (2014), Raw (2016), Midsommar (2019), A Quiet Place (2018), Us (2019), The Invisible Man (2020) or The Neon Demon (2016). Many recent and highly acclaimed films that aren’t thought of as horror have undeniable horror elements like The Lighthouse (2019) or Parasite (2019) – and the latter won the Oscar for Best Picture.

In series or streaming we have American Horror Story (2011), The Walking Dead (2010), Penny Dreadful (2014), Squid Games (2021), Supernatural (2005), Stranger Things (2016), Dark (2017) and Midnight Mass (2021), a series so well written and acted and which plays its genre cards in such subtle, unhurried fashion you’re not even completely sure what you just watched when its over – you just know how astonishing it is.

It’s a loaded question but given the above list, has horror actually been bucking the existing-IP trend and getting better in the last couple of years? “It’s fresher,” Garris agrees. “The American studios want franchises, they don’t want fresh, original stories, and to me the most successful movies are the ones you haven’t seen before.

“There’s more diversity in horror now but it’s because of the multiple platforms, not the studios – the Netflixes, Amazons, Hulus and Shudders of the world. There’s a place for original horror that there didn’t used to be.”

And that’s because great horror, Garris contends, is great drama first, something plenty of directors fail to grasp. He talks about Misery (1990), which contained an Oscar-winning performance from Kathy Bates, and Rosemary’s Baby (1968) as just two examples. “There’s no more horrific movie, but it’s also a mainstream drama, it only becomes really scary if you meld the two.”

And like many genuine horror devotees, he rejects the term ‘elevated horror’, something that’s entered the lexicon over the last few years because of cineastes too ashamed to admit to liking genre films. “It’s snobbish, it denigrates the genre,” Garris says. “Good horror is just good horror. Anyone who does horror and says ‘ours is elevated’, I find that to be insulting.”

At the same time, streaming services – and clever studios – are realising something else about horror these days. The cost of acquiring shows and movies is dropping thanks to the explosion of networks and streamers (which means more buyers), and that means there’s a wider demand for niches.

One of those niches is the power of fandom. Marvel could never afford to spend $200m on comic book movies if they only appealed to hardcore comic nerds. But while those of us who came of age in the slasher or video nasty era worship names like Hooper, Gordon, Cronenberg, Carpenter, Romero or Dante, it’s easy to forget they didn’t have mass appeal. That’s why so many of them spent their careers battling with studios who only had one target – the mainstream – no matter how revered they were by fans.

Now, because the new entertainment business can cater to niches, a genuine love of movies and genres seems to be leaching into the executive ranks and greenlight committees. Among the many reasons we lost some of the horror greats like Hooper, Craven and Romero too soon is because Netflix or Shudder might have been smart enough to give them the creative freedom they never got in their careers.

We’ll never know, but Garris is heartened by the fact that he was able to give some of those legends that experience. “[In many cases] the last things they did were for Masters of Horror. It’s a beautiful idea. One of the things I appreciate most was being able to provide a platform to those people I admire so much.”

There’s horror, and then…

But Garris’ oeuvre raises another interesting genre question, especially now writers and directors can be far more extreme because there’s more than just linear TV and cinema. What exactly is horror?

The question doesn’t refer to the whole ‘elevated horror’ debate/debacle, but the place of extreme elements in the genre – the stuff that, to many, makes horror what it is. Garris remembers ABC’s ‘no open eyes on corpses’ rule with a chuckle, calling the slow zoom into the dead, frosted-over eye of the lab technician during The Stand’s credits he and King’s ‘middle finger’ to the network.

Today films and series on streaming or cable can depict nudity and sex scenes, lopped-off body parts and gore splattering the walls like it’s coming from a high-pressure sprayer with gleeful abandon. But on The Stand and The Shining, Garris had to be scary without all that. Is that a ‘purer’ way to make horror?

“It’s a great point,” he agrees. “It’s easy to fall back on special effects and that can be great for recreational horror, but the storytelling has to be strong. Like I said before, great horror is great drama and you should get sucked into the storytelling. Sometimes something can seem extreme because it sticks out from the story. If something extreme is organic to the story, including it doesn’t feel as transgressive because it’s part of the storytelling itself.”

In fact, extending the idea that horror is getting better, it’s a mantle plenty of great directors are running with recently, challenging themselves to be scary without resorting to boobs, beheadings or jump scares. When talking about the influence Garris’ work has had on him, Flanagan says it goes right back to The Stand, which showed him what long form horror could really be.

“[It’s about] the depth of character, the sense of truly epic storytelling. Mick understands something about horror a surprising number of storytellers don’t – the importance of love and empathy. Stephen King understands that as well, and it’s one of the reasons he’s chosen Mick to adapt more of his work than any other filmmaker.

“There has to be a sense of humanity, a beating heart. Beauty to balance the ugliness, a sprinkle of hope to contrast the horror. In The Stand Mick prioritised the human moments of the loss, the grief, the humanity of it all. At 16 I was bowled over by the idea I’d be crying at a ‘horror’ series. That blending of heart and horror forever tattooed my work and I can see the influence all over it to this day.”

Taking it personally

For now, Garris is still a jobbing writer and director, and we’re a little disheartened to hear that he still has projects fall over at the eleventh hour, get stuck in development hell or has bad experiences with producers he subsequently doesn’t want to work with again. We asked him about the forthcoming projects on his imdb.com page and they’re almost all dead in the water.

10 or 15 years ago it might have been easier (it’s never been ‘easy’, mind you) for a director of Garris’ standing to get projects greenlit, but in one sense it’s the industry that’s moved on. Unless you’re a Nolan, Spielberg, Scorsese or Fincher you only have so much creative control. In fact the latter two have themselves gravitated to streaming services – Netflix is the only one that would give them the budgets to realise their ambitions for The Irishman and Mank.

And a lot of what’s left in the world of cinema means uber-producers like Kathleen Kennedy or Kevin Fiege are the real creatives, the directors ending up mere technicians Garris thinks the execs are ‘able to influence more directly and have a little more control over, pay them less and that sort of thing’.

But a combination of more outlets than ever before and his irrepressible love for what he does means there are plenty more irons in the fire. Another Stephen King adaptation that came close to happening years ago is looking up again. He and Clive Barker are creating a series based on original Barker stories that’s found a home on a network.

Then there’s the production company that’s optioned what he describes as his favourite script, a period piece he wrote 30 years ago and spent some of 2021 rewriting completely, and a two-hour pilot for a series called Graphic which he describes as being unlike anything else we’ve seen from him (more below).

And that’s just in films. He’s still writing novels, one of which (Salome) is being adapted for a podcast series, and Post Mortem has filled a lot of his hours and the creative urge the last couple of years, especially during the worst of the pandemic. He and the other members of his band from the 70s, Horsefeathers, even got their best recordings together and finally put out their debut album.

“I’m hoping these projects work out, but the norm is for something to not happen,” he says of movie and TV projects on the boil. “If you create hit after hit you’re safe, but if you’re an independent filmmaker or someone for whom it’s been a few years, your ability to set up whatever you want isn’t high, and during the 30 years or so I’ve been doing it you just create the opportunities and see what happens.”

When we talk about directors who refuse to compromise to formulaic studio filmmaking and make art that matters to them we think of names like Terry Gilliam, Stanley Kubrick, Lynne Ramsay or Spike Lee.

You might include Garris among them because everything he does means something to him. He’s talked often about how Riding the Bullet is his most personal film because it helped him process the grief of death in his own family.

Then there’s Graphic, a story about a kid who discovers his father was a great artist. Like the father in the story, Garris’ dad was a very talented comic book artist who gave up on it because he couldn’t rely on it to provide for his family. They’re just two examples of how Garris seems to apply himself 100 percent to whatever he’s working on.

“I don’t know how it’s possible not to,” he says. “It’s really hard to make films and television. The hours suck and if you can’t be completely committed to surrounding yourself with creative people and trying to make something special, what’s the point? If you’re doing it for the money that’s going to end very quickly – if it ever begins. But if you’re doing it out of love and passion and sharing this experience with people you admire, what better life is there?”